A Relic of the Past?

2 December 2021

The trade in religious relics might seem medieval, but it is still going strong.

Fergus Butler-Gallie

The Reverend Fergus Butler-Gallie is a clergyman and the author of A Field Guide to the English Clergy, a Best Book of the Year for The Times, Mail on Sunday and BBC History.

Baroque reliquary with relic of the True Cross and nail-relic with their original documentation, 18th century, Italy, 20 cm x 38 cm x 15 cm.

Image courtesy of Fluminalis.

If you were running a cathedral in continental Europe whose popularity was dependent on a relic during the Nineteenth Century, the last person you wanted turning up on your doorstep was the Reverend William Buckland. The Anglican cleric specialised in bursting bubbles: when he turned up in Palermo he visited the shrine of St Rosina, whose bones were held to be relics with power to protect against the plague. Buckland- who was on his honeymoon at the time, the old romantic- spent a day inspecting the relics only to declare that they were, in fact, the bones of a goat. Still, St Rosina fared better than one unnamed local French saint whose miraculous blood Buckland inspected by licking it only to declare that it was not blood at all but ‘a taste that he would recognise anywhere’- bat urine.

Despite the contempt of rationalists like Buckland, relics remain a source of endless fascination for the faithful and faithless alike; and where there’s fascination, there’s a market. Christian relics have been bought, sold and stolen since the very earliest times, with often high prices and high risks involved- the body of St Mark was illegally removed from Muslim Alexandria to Christian Venice by wrapping it in pork fat. From the Pardoner in the Canterbury Tales to Archbishop Edmund in Blackadder, those who have sought to make money from relics (legitimate or otherwise) have long been stock characters in depictions of the Medieval world.

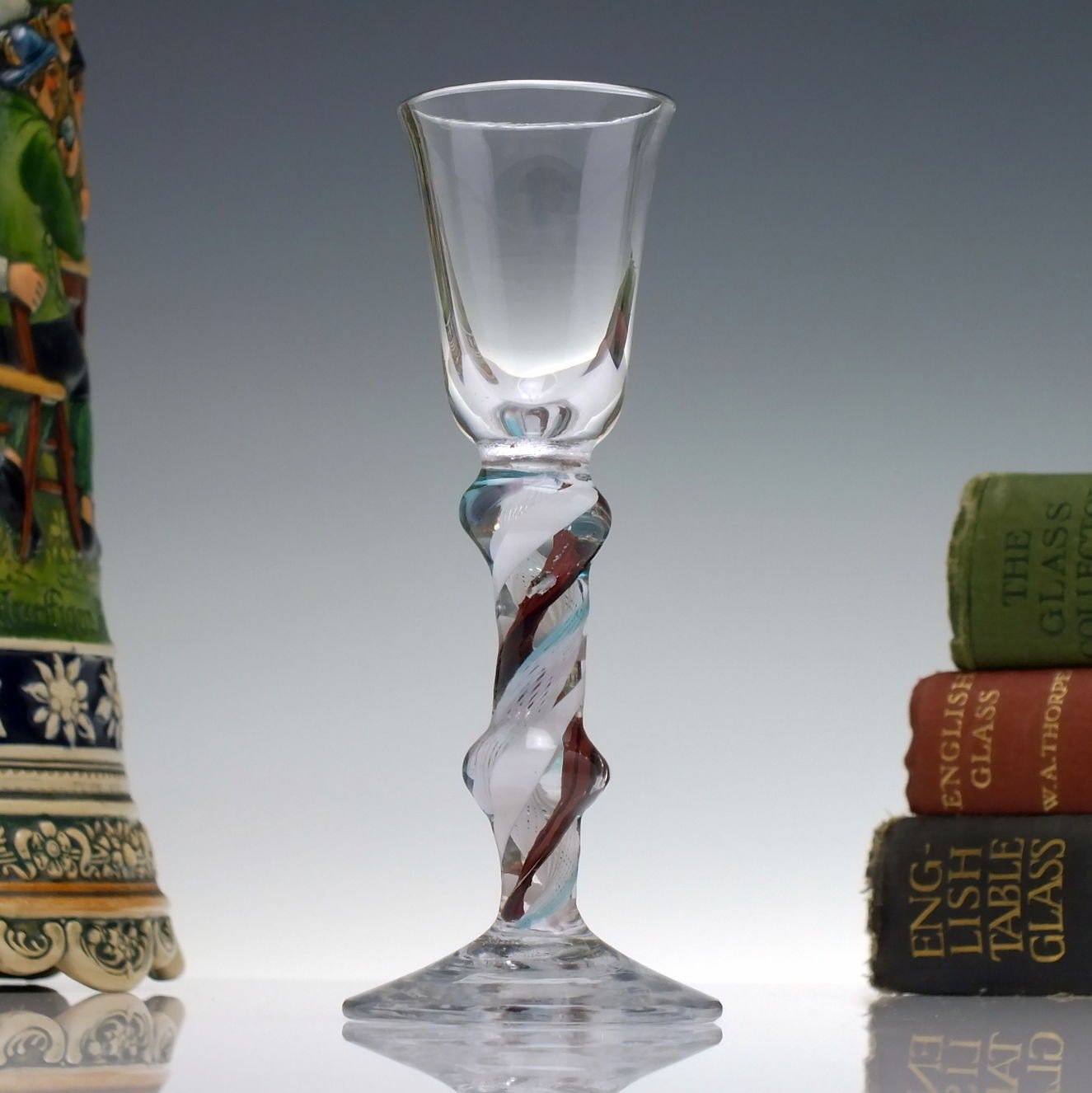

Yet, this trade is not just, if you’ll excuse the phrase, a relic of an era long gone. The trade in bits of saints continues to this very day. In 2014, at a Sotheby's medieval art sale, reliquaries containing locks of hair from Saint Sixtus II, St Agnes and St Ursula sold for £559,500 (from an initial estimate of £80,000). Meanwhile, via Fluminalis- one of the world’s relic specialists- you can buy bits of, inter alia, St Gertrude, St Anthony of Padua and the Martyrs of Gorkum complete, of course, with pieces of paper sealed with wax and adorned with elaborate coats of arms showing that these are the real deal. Prices are on application.

When it comes to working out what constitutes a genuine relic, provenance is as big an issue now as it was in Buckland or Chaucer’s times. Often a certificate from the Vatican is considered enough for most buyers. There are ranks- primary, secondary, tertiary. Roughly speaking these mean: body parts of a saint as the top tier, then items used by a saint and finally, objects that had been in contact with either of the other two. Papers can make a huge difference in pricing: at A R Broomer, a now closed shop in the Manhattan Art and Antiques Center, a piece of bone with papers could fetch around $2,500, whilst one without would struggle to make $500. Confusingly, of course, there are those saints whom the Roman Catholic Church considers to be holy but others, such as the Orthodox Churches or Anglicanism, do not. There’s further confusion when multiple saints have multiple authorised relics- there are, for instance, whole or partial heads of St John the Baptist in Rome, Amiens, Istanbul, Munich, Montenegro and Damascus. The final one is in a mosque because, as if the varied approaches of multiple Christian denominations weren’t complex enough, Islam considers him a saint and, as a faith, incorporates relics as well.

A reliquary bust of a Virgin Martyr, c. 1480 - 1500, Switzerland, brass alloy with gilding and polychromy, 43.5 x 43 x 25.5 cm.

Image courtesy of Sam Fogg, London.

Reliquary arm relic of St. Dominica, silver / brass, 18th century, Southern Germany, 14 cm x 37 cm x 14 cm.

Image courtesy of Fluminalis.

Questions of authenticity become even more of an issue when the sourcing of the relics is not, shall we say, on the open market: when John Henry Newman was declared a saint by the papacy in 2019, an Oxford College which housed a number of his letters discovered devout Catholics were removing them from the library in which they were stored by stuffing them up their jumpers and then using them as relics.

Of course, it isn’t just the relics themselves that attract buyers. I was surprised to come across a whole selection of reliquaries- the elaborate sculptures that hold relics- at the super trendy Frieze Art Fair this year. These were shaped like the heads of the saints whose relics they contained and were exhibited there courtesy of Sam Fogg, the medieval art and sculpture specialist. Again, prices are high enough to only be shared upon application.

If such prices are beyond you then fear not: there’s always Ebay. Among the many bits of holy men and women that can be found in the online auction house’s listings is a reliquary with 15 assorted relics of saints. This will set you back a mere £1,100 or just over £73 per relic. Helpfully the seller has marked clearly that they are ‘used’. Well, you’d certainly hope so. If you fancy a bid on them, just don’t ask William Buckland round to authenticate your winnings.